Huang Jia is a contemporary artist who lives and works between Berlin and Shenzhen. she has been active in the Chinese contemporary art scene since the landmark ’85 New Wave movement and is widely regarded as a leading figure in post-minimalist conceptual painting in China.

Huang Jia’s work has been presented in numerous international exhibitions and art fairs across the United States, Europe, and Asia, including Berlin, Zurich, Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong. She has also held multiple solo exhibitions and participated in major events such as the Berlin Art Fair, Shanghai 021, West Bund Art & Design, Art Beijing, Art Shenzhen, and the Korea International Art Fair (KIAF).

Her practice has been featured in major art publications such as A History of Modern Chinese Art, Contemporary Art, The Artist, Art Monthly, Art Vision, ASIAWEEK, and CITYLIFE. Huang Jia’s works are included in the collections of museums, art institutions, and private collectors worldwide.

Huang Jia

Painter

Huang Jia: Artistic Trajectory

Stage One: Creative Exploration (1981–1985)

Leaving home for university brought Huang Jia a brief liberation from the emotional restraints of her earlier life. With her crisp short hair, she often led her classmates in nightly still-life sessions and outdoor landscape studies. Influenced by artists such as Vincent van Gogh, her works from this period burst with dynamic tension and lyrical movement. Her use of color was both poetic and expressive—imbued with the warmth of humanity and the sensitivity of nature.

During this stage, Huang Jia also began to turn her gaze toward the lives of women around her and the various forms of oppression and social phenomena they faced. Through the outpouring of her own emotional experience, she gradually began to perceive the intellectual and spiritual strength inherent in women themselves. This awakening laid the conceptual and emotional groundwork for the next phase of her artistic development.

Stage Two: Awakening of Female Consciousness (1985–1995)

In the decade following her graduation in 1985, Huang Jia gradually constructed, through painting, a profound and intimate world of feminine subjectivity. In series such as Women and Shoes, Women and Ashtrays, and The Laughing Lady, the female subject steps forward—not as an object of the gaze but as an agent of perception and self-awareness. Her art departs from the grand political narratives of “women’s liberation” and instead turns toward private, embodied experiences of womanhood. This shift echoes theoretical discussions of “the body as a site of gender performance,” allowing Huang to reconstruct female identity through personal sensation, pleasure, and autonomy. Her works challenged the conventional tropes of victimhood and moral didacticism often imposed on women’s art, aligning more closely with post-feminist explorations of multiplicity and subjective diversity.

In these years, Huang intentionally stripped her compositions of superfluous elements to create a purified yet enclosed psychological space—one that amplifies the interior state of the female subject. Her use of large color blocks, contrasting tones, and mysterious lighting conveys metaphors of sexuality, solitude, helplessness, and alienation. In the Waiting for Hairstyle series, for example, a bald young woman inhabits a static yet perpetually generating enclosed space, her melancholy gaze directed beyond the canvas. This figure reflects countless women confined by shame and social constraints—figures whose relationships are fraught with contradiction, desire, and insurmountable distance. Through this imagery, the female self undergoes an expansion, reaching toward a broader existential dimension.

Huang’s intense color language and exaggerated forms evoke an unsettling visual tension that stirs the viewer’s psyche—one feels directly the oppression and vulnerability that underlie women’s lived experience. Yet her art is not merely an expression of personal emotion; it also mirrors the awakening and predicament of female consciousness in the social context of China’s early Reform era.

Amid the ideological currents of 1980s humanism and intellectual liberation, Huang painted from a distinctly female-centered perspective. She captured subtle shifts of body and psyche, challenging both traditional painterly conventions and entrenched gender narratives. Her depictions of bald, androgynous women—framed within geometric structures, shadow projections, and dramatic subject–object relations—suggest a dialogue between solitude, desire, and the tensions within female consciousness under historical conditions.

By eliminating visual excess and creating space for imagination, Huang exposed the everyday entanglement of desire and repression. She blurred the boundaries between self and other, establishing an artistic domain that oscillates between identity inquiry and psychological realism. In this space, her art achieves philosophical resonance—one that transcends representation to engage with being itself.

Stage Three: The Life of Women (1996–2006)

Modern urban life, characterized by its accelerated tempo and pervasive vigilance, magnifies both material desire and spiritual exhaustion. In this high-speed circulation of satisfaction and alienation, human souls are caught in an endless cycle of convergence and separation. Yet Huang Jia did not yield to the frustrations of life; rather, she found rebirth through painting—her unique medium of introspection and resistance. Over this decade, she wielded art as a scalpel to dissect the surface of women’s lived realities, confronting the spiritual anxieties and emotional impasses embedded in the machinery of modernity.

As an individual within the broader spectrum of contemporary womanhood, Huang maintained a dual gaze—turning both toward her sisters and inward toward herself. She rejected the conventional visual paradigm of feminine gentleness and resisted the lure of commercialized sensuality in art. Instead, she adopted a lucid, even brutal brushwork to expose the psychological pressure and identity crisis endured by individuals within the process of urbanization. In series such as Laughing Woman and Smoking Woman, she created portraits of young women who are at once alluring and weary, empty yet resilient.

To capture the most authentic contours of women’s lives, Huang laid bare their fragile, distorted inner worlds without euphemism. Through her depictions, we confront the cruel, unrelenting forces that women must endure in reality. The fashionable, languid, and decadent female bodies in her canvases—at times hollow, seductive, or numb—become transparent vessels through which the artist reveals “Her” essence. “She” is helpless, anxious, fearful, and yet irresistibly magnetic—vulnerable but unyielding.

A profound transformation occurred around 2003, when Huang became a mother. This experience initiated a quiet internal shift. In works such as Daily Life, Hula Hoop, and Companions, her once sharp and austere perspective softened, replaced by the luminous tenderness of maternal awareness. Her paintings began to flow with intimacy, playfulness, and affection—the innocent companionship of children emerging as a new subject. This change was not a retreat but an expansion: a continuation of feminine consciousness into a new realm of life experience.

Through this transition—from critique to empathy, from dissecting pain to embracing the everyday—Huang realized an inner crossing: from self to others, from confrontation to reconciliation. Her art in this phase no longer sought to expose wounds but to understand them, transforming painting into a space of emotional healing and quiet strength.

Stage Four: Spiritual Exploration (2006–2015)

As the twenty-first century unfolded, Huang Jia’s art entered a new phase marked by philosophical reflection and profound inner stillness. Confronted with the rapidly shifting cultural landscape and the intensifying weight of reality, she turned away from explicit depictions of the body and desire. Instead, her focus shifted toward the quiet observation of everyday minutiae and the questioning of perceptual authenticity.

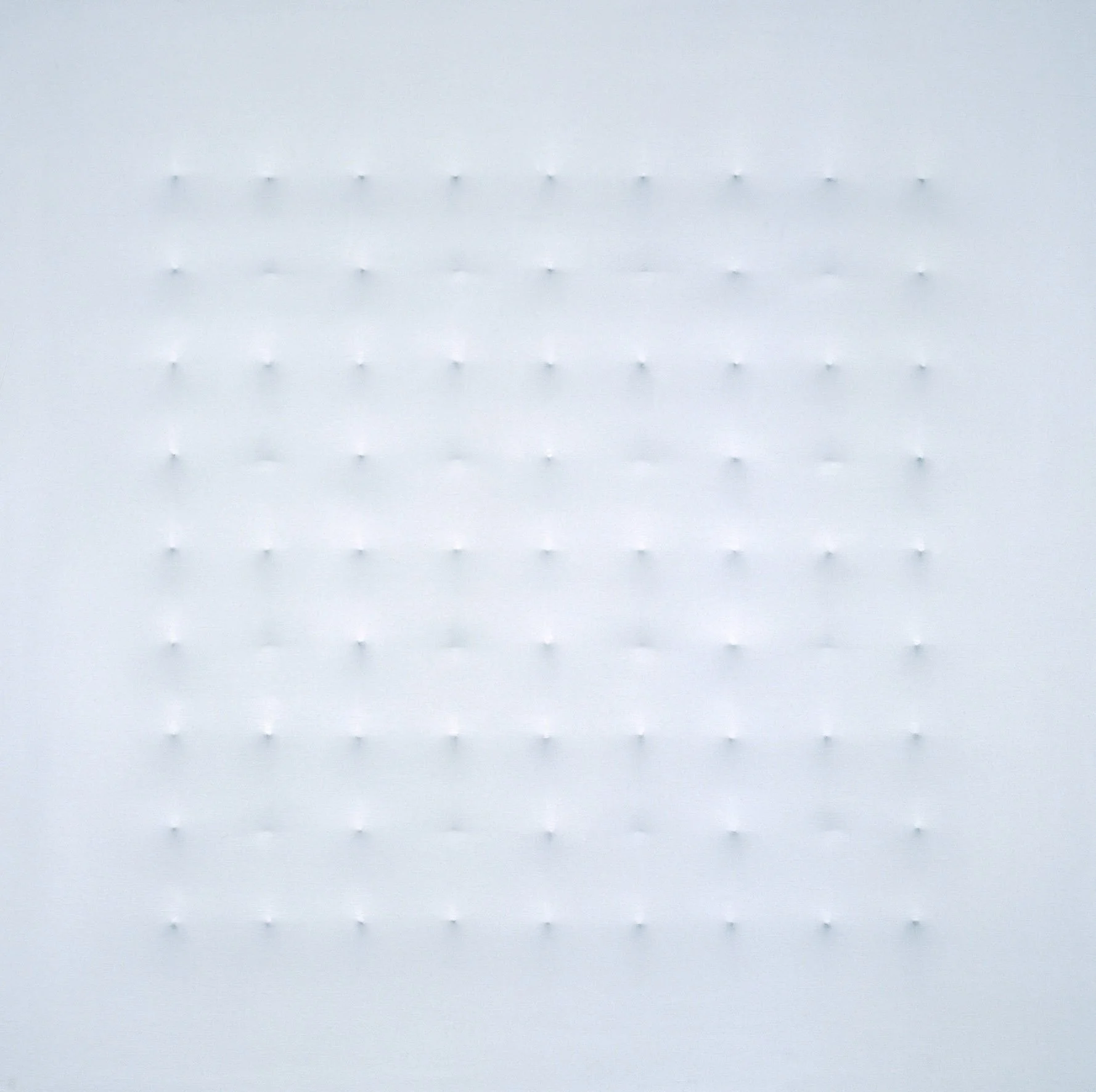

Huang began to paint small, often-overlooked objects—a pushpin, a paper clip, a droplet on the refrigerator, a pattern of raised dots, or a toy suspended between reality and illusion. These unassuming elements ceased to carry emotional drama; they became instruments for probing the tension between being and appearance, between existence and illusion.

Influenced by Western skeptical philosophy, particularly the epistemological inquiries of David Hume and Immanuel Kant, Huang sought to reconstruct a mode of experience in which reason and perception coexist in delicate balance. In her Suspicion Series (2007), meticulously arranged dots and convex forms deliberately destabilize the viewer’s sense of visual certainty, compelling reflection on the reliability of the so-called “objective” world. The cool, repetitive points are not mere abstractions—they function as psychological signals, visual manifestations of the collective unconscious, transmitting inner tremors and spiritual resonance through the simplest of forms.

In this phase, Huang no longer shouted through color or gesture. Instead, she spoke through silence, order, and subtle variation, guiding the viewer toward introspection and contemplation. She once remarked:

“The point and the line can be understood as the existence of illusion. As the viewer examines each subtle variation, the corrosion of life by both reality and illusion becomes at once clearer and more obscure. What seems empty in the work is, in fact, essential—existence, vision, and imagination together sustain creation.”

For Huang, form itself became grammar. Beneath the monochrome, minimalist, geometric surfaces of her canvases, warmth and humanity quietly persist. Through the dilution of narrative and the restraint of color and emotion, she sought a sanctuary of the soul beyond noise and spectacle—a spiritual repose that derives its strength from stillness and reaffirms life through doubt.

Her art thus evolved from the “expression of pain” to the “inquiry into truth,” marking a profound shift from emotional articulation to conceptual contemplation.

Stage Six: Time, Space, and Endurance (2016–2022)

In this period, Huang Jia’s artistic practice arose from a deeply modern dilemma—“We no longer know how to face ourselves.” Her works reflect a collective crisis of self-identity in an era where traditional references have collapsed. As she observed, only by questioning the meaning of life can one begin to discover it. The “correct answer,” she suggests, lies not in external validation but within the self—waiting to be uncovered through endurance and introspection. Her art thus becomes both an inquiry into and a response to the inner anxiety of contemporary existence.

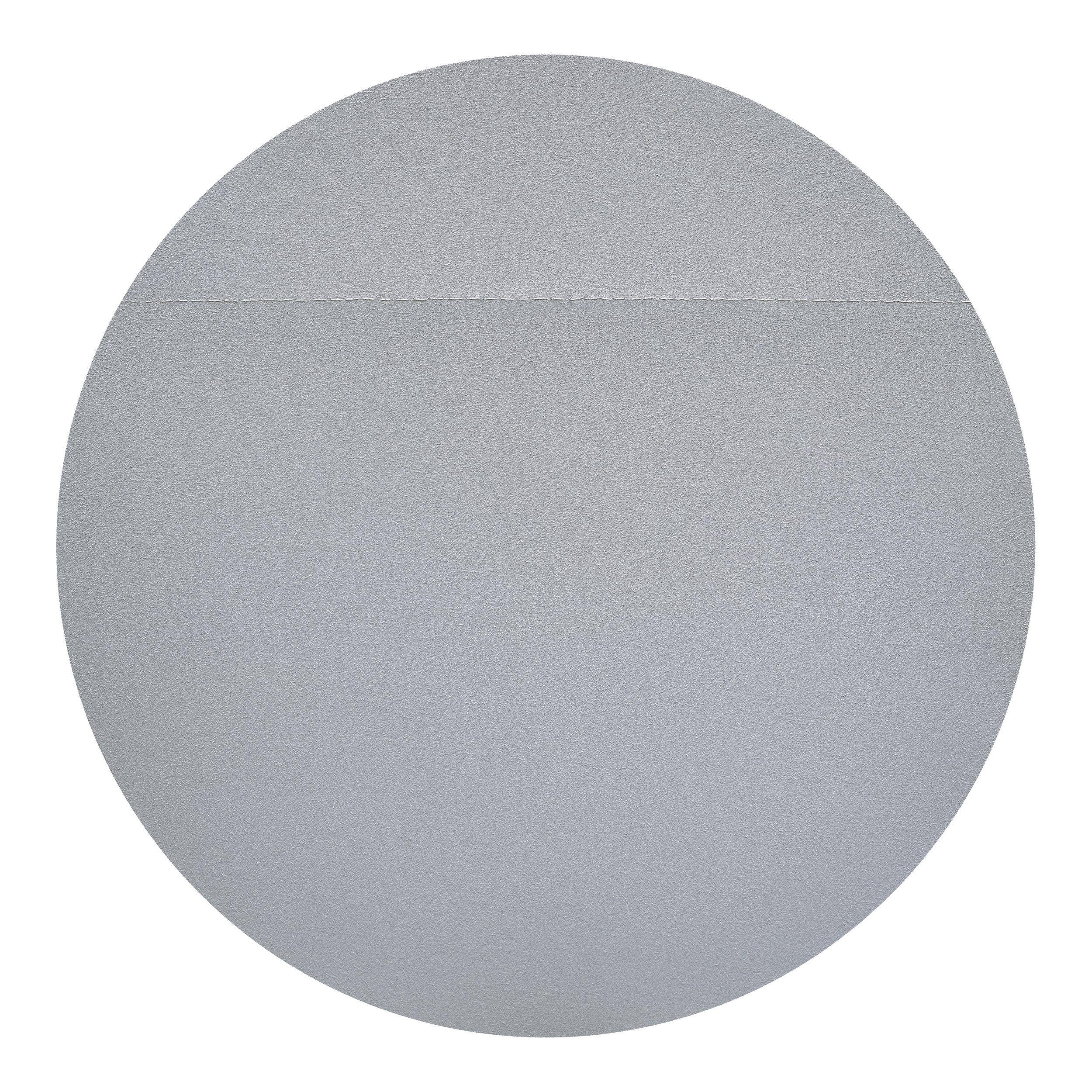

Huang sought to construct, through the simplest visual elements—dots, lines, and planes—a holistic spatial relationship capable of evoking vast imaginative depth. In her Veiled Time series, she employed acrylic on canvas to explore the hidden, layered, and malleable nature of time itself. These works metaphorically engage with the accumulation of memory, the processes of trauma and repair, and the resilience of personal history.

In several pieces, Huang introduced stitch-like brushstrokes and literal sewn threads into her compositions. The act of stitching became a narrative of boundaries and survival. Inspired by Southeast Asian textile traditions, she sometimes built up pigments to mimic embroidery, while at other times sewed directly into the canvas. The resulting interplay of material and illusion produced subtle visual ambiguity—simultaneously tactile and ephemeral. Simple geometric forms—circles, squares, or a single unbroken line—served as structures that bridge tradition and contemporaneity, material and spirit. The use of historically resonant hues such as celadon green and colors drawn from ancient ceramics imbued her works with cultural depth and luminous spirituality.

These thread-like reliefs, raised subtly from the surface of the canvas, function as both physical traces and metaphors for the dialectics of healing, memory, and the passage of time. The linear motion of stitching echoes the calligraphic spirit of feibai (flying white), infusing geometric order with the warmth of human touch. By incorporating the feminine craft of sewing—a symbol of domestic labor and care—Huang reconnected this phase of her work to the feminist roots of her earlier practice, but now transfigured through a meditative and transcultural lens.

In the Into Time series, Huang’s monochromatic surfaces breathe with delicate tonal gradations, evoking an atmosphere of emptiness and quiet illumination. Her whites are never absolute; they contain imperceptible variations of cool and warm tones accumulated over time. These layers resonate with the Daoist cosmology of “xu shi sheng bai” (from the void arises clarity). The temporal dimension of her painting operates invisibly: each layer of pigment, applied and dried hundreds of times, records a hidden chronology—a secret chronology of patience. For the viewer, time unfolds through prolonged looking. Subtle pulsations of light and color become perceptible, countering the instantaneity of digital culture. Her paintings are silent yet radiant, embodying both serenity and strength—an affirmation that endurance itself can be a spiritual act.

Stage Five: Dislocated Space (2023–Present)

In her most recent Dislocated Space series, Huang Jia has developed a distinctive and conceptually complex visual language. She deliberately subverts traditional laws of perspective, constructing on a two-dimensional plane a space that appears both plausible and paradoxical. Lines and planes intersect, overlap, and invert; parts embed within wholes even as the whole seems fractured by its fragments. The result is a visual experience akin to non-Euclidean geometry—an unstable yet harmonious coexistence of order and disarray.

Outwardly, these works appear calm, rational, even restrained. They are often composed of simple lines, geometric blocks, and minimal chromatic zones. Yet beneath this minimalist surface lies a quiet rebellion against visual convention. Huang’s compositions destabilize the viewer’s sense of spatial certainty and challenge the logic of perspective that has governed Western pictorial space since the Renaissance. The relationship between part and whole becomes fluid and reciprocal—each element simultaneously defines and dissolves the other.

In this subtle yet radical practice, Huang is less concerned with representing objects than with questioning the conditions of perception itself. The dislocation in her paintings is not merely formal—it points to existential and cognitive displacements endemic to contemporary life. By dismantling familiar visual hierarchies, she creates an open system in which geometry becomes both spatial and psychological: a site where intuition and logic, emotion and order, cohabit in fragile equilibrium.

Through Dislocated Space, Huang extends her long-standing inquiry into time, memory, and being into a new dimension of spatial thought. The cold precision of her lines conceals an undercurrent of human warmth; her geometry, though rational, is never mechanical. It breathes with the subtle rhythm of thought and the quiet pulse of feeling. These works do not offer resolution but invite contemplation—they are propositions about how one might inhabit uncertainty, and how meaning might emerge precisely from dislocation.